Interviewer: King Bo, thank you for being here. Let’s start at the beginning. How did Cut by the Border come into being?

King Bo Wang: Thanks for having me! Honestly, it wasn’t some grand plan. I was just tagging along on a trip to Tijuana with my dad, thinking I might ask someone about tariffs or something “business-y.” But then I met Chava, working at a cardboard factory. He spoke perfect English and had this quiet confidence about him. When he told me he’d been deported at 18, right after 9/11, over something minor, it kind of stopped me in my tracks. I just asked if he’d be willing to talk more. One question turned into hours. Next thing I knew, I was deep into a story I never expected to find.

Interviewer: You’re 17, still in high school. Yet, Cut by the Border is a remarkably mature piece of work, dealing with layered issues of migration, justice, and identity. What made you, as a student, take on something this complex?

King Bo: Honestly? It sort of found me. I wasn’t out to make a film about deportation or immigration policy or anything like that. I just listened to Chava, and his story stuck with me. I realized, if I just moved on and pretended it never happened, I’d basically be adding to the silence he was talking about. I’m not a politician, and I definitely don’t have all the answers. I’m just a teen with a camera. But I could pay attention, and I could try to make sure his voice got heard. That felt like enough to start.

Interviewer: You’re very intentional about giving space to people’s voices. How did you build that trust within your subjects?

King Bo: I tried to make it feel less like an interview and more like a conversation. No lights, no scripts, just hanging out and talking. I always made sure they could see what I was recording, and if they wanted to stop, we stopped—no pressure. I’d show them clips as I edited, just to make sure they felt good about what was in there. Trust isn’t something you can rush; it builds if you keep showing up and listening for real, not just waiting to ask your next question.

Interviewer: You chose to include your own voice in the documentary as voice-over. That’s not something all young directors would feel confident doing. Why did you make that choice?

King Bo: That decision kept me up at night! I really didn’t want to turn it into “the King Bo journey in Mexico.” But after a while, I realized that pretending I wasn’t there was also a choice. Silence isn’t neutral—it says something, too. My voice ended up being a bridge between my interviewees and audience: not taking over, but letting viewers in on what it’s like to listen, as someone who’s maybe not supposed to be part of this story. I guess I wanted to be honest about where I was coming from.

Interviewer: In the film, you’ve also interviewed some of Chava’s co-workers. One of them says, “You have to learn to stay invisible.” That’s a line that says a lot without making a fuss. How did that moment strike you as a filmmaker?

King Bo: That line hit hard. It made me realize some folks have to blend in, not because they’ve done anything wrong, but because it’s safer that way. For some people, keeping your head down is just basic survival. It really made me think about how much people adapt to circumstances, sometimes in ways nobody even notices.

Interviewer: Your film also includes insight from Dr. Linford Fisher, a historian at Brown University. He talks about how the U.S.–Mexico border wasn’t always fixed, and the movement used to be normal. Why did you feel it was important to include that historical perspective?

King Bo: I think it’s easy to forget the border hasn’t always been what it is now. Dr. Fisher’s perspective really blew my mind—I hadn’t thought about families just going back and forth like it was no big deal. And what he said totally lined up with what Rosendo, the factory guard, told me in our interviews. He talked about riding his bike across the border in the 90s—no big deal, just like visiting the next town. Hearing that made Chava’s story feel bigger. It’s not just about one person, but about a whole history of movement that got way more complicated over time. I wanted the audience to have that “wait, what?” moment too, where you realize how much things have changed.

Interviewer: Did it change how you view the concept of a border?

King Bo: Oh, for sure. Before, I thought borders were just big lines on a map, and that was that. Now I see it’s way messier—there are physical fences, yeah, but also all these invisible lines people deal with, like cultural stuff, laws, even how people treat each other. Some borders you see, others you just feel.

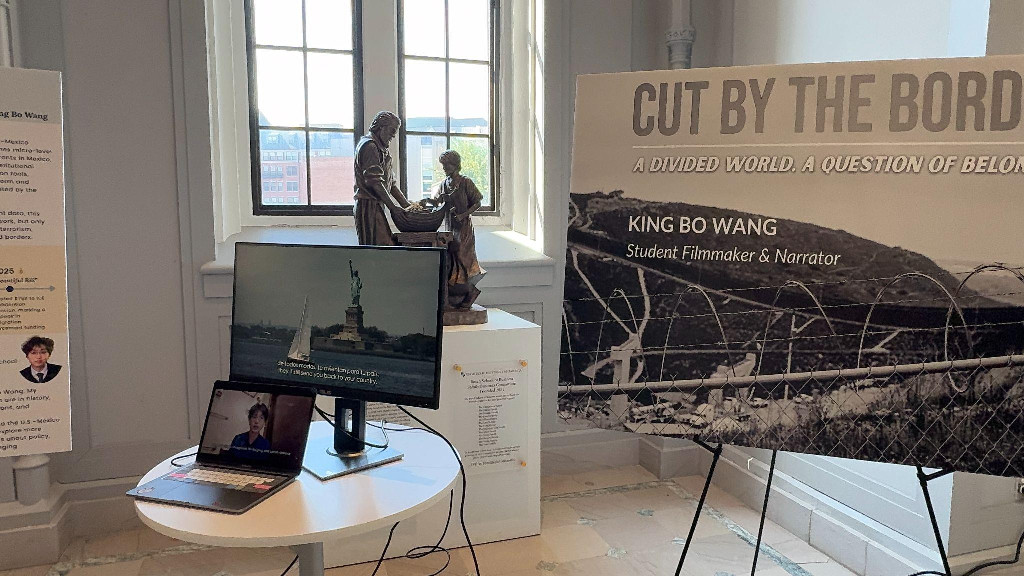

Interviewer: In addition to the film, you also created a companion series of black-and-white photographs titled Cut by the Border. Can you talk about what drew you to still photography, and what you hoped to capture with these images?

King Bo: For me, sometimes a single photograph can hold a whole story, even without words. While I was in Tijuana, I kept finding moments that felt impossible to explain with video alone—things like layers of missing person flyers peeling off concrete, locals on their phones just feet from the fence, or fruit vendors working right by the beach while seabirds flew past the border wall. The photos are kind of my way of slowing things down. I just wanted to show what I saw, and maybe let people draw their own conclusions about life at the edge.

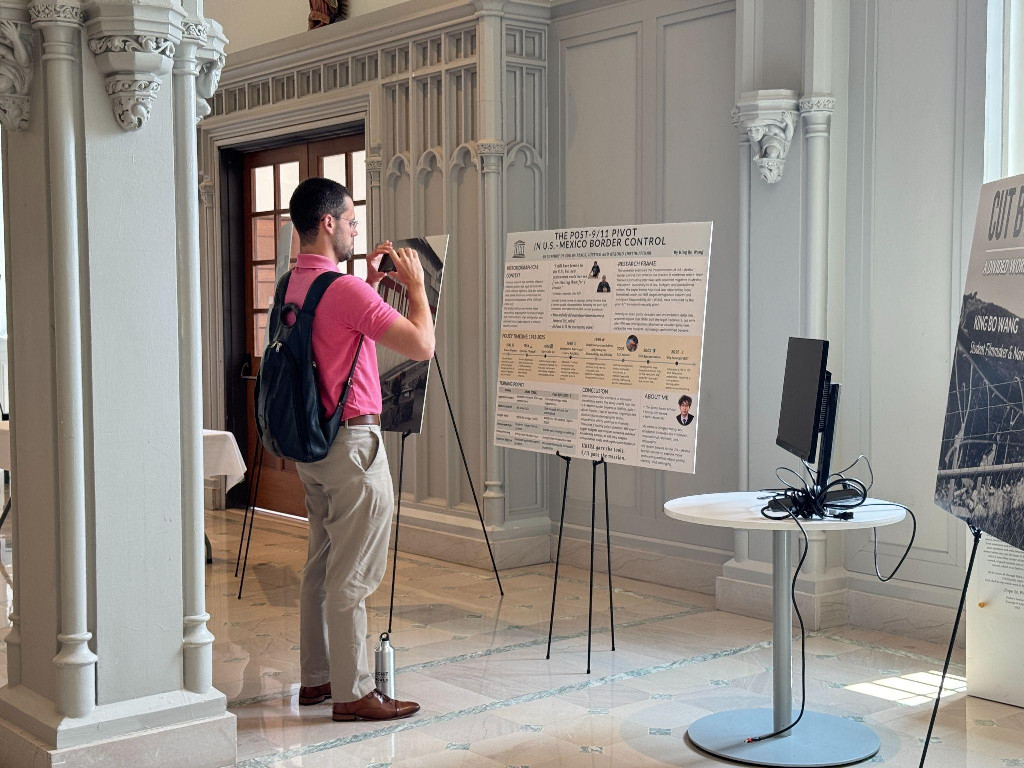

Interviewer: The film and your photos focus a lot on individual stories, but you also did a historical research paper for this project. What made you want to dig into the history behind these personal experiences?

King Bo: When I started listening to Chava and his co-workers sharing experiences, I realized these weren’t just isolated stories. There’s this whole system behind them. So, I wrote a research paper tracing how U.S. immigration and deportation policies have changed over the last century. Talking with Dr. Fisher, who appears in the film, was very helpful. He pointed out that the border didn’t used to be this hard line—families could cross all the time. It was only after things like 9/11 that the border got way tougher. That history totally changed how I saw the present. It’s like the saying: “We didn’t cross the border—the border crossed us.”

Interviewer: Your project is featured on UNESCO’s youth platform, and it ties into SDG 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions. What question did you want people to walk away with?

King Bo: To be honest, I never wanted this project to hand out answers or deliver a lecture—no one really enjoys being lectured, after all. My goal was more to invite people in, to share a moment of curiosity about how borders and histories we didn’t choose can quietly shape our lives.

If someone finishes experiencing my work and finds themselves thinking, “Huh, I never considered how much of my own story was decided before I noticed,” that’s a win in my book.

At the end of the day, I think it’s less about giving conclusions and more about sparking the right questions. Maybe the real challenge is: How do we keep finding meaning and connection, even when life keeps drawing new lines between us? If my project leaves people reflecting even just a little, then in my heart, I’ve done my job.

Interviewer: Do you have anything else to share that was particularly meaningful/important in this project?

Kingbo: I have to thank my school, Stony Brook School. In my freshman and sophomore years, my teachers questioned: “What is the good?” and “How can we achieve the good?” In my junior year, I took college-level ethics and politics, further requiring deep thought and reflection. Our teachers graded us less on answers than on the clarity of our reasoning, the courage to revise, and the empathy we showed toward opposing views. Thus, when I came to Tijuana, Mexico, I felt the urge to make another inquiry, another attempt to translate complex systems into a human scale. I believe that it was SBS that taught me this ability.

Ending

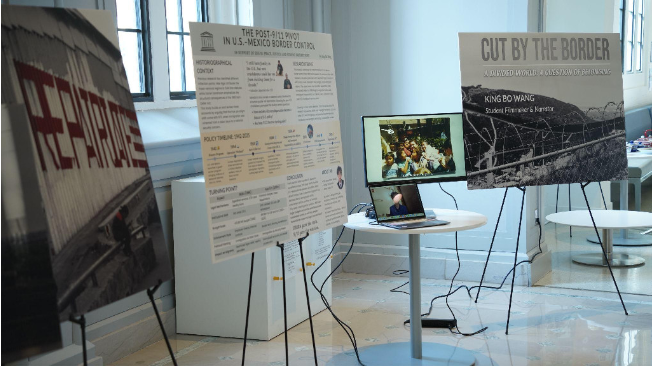

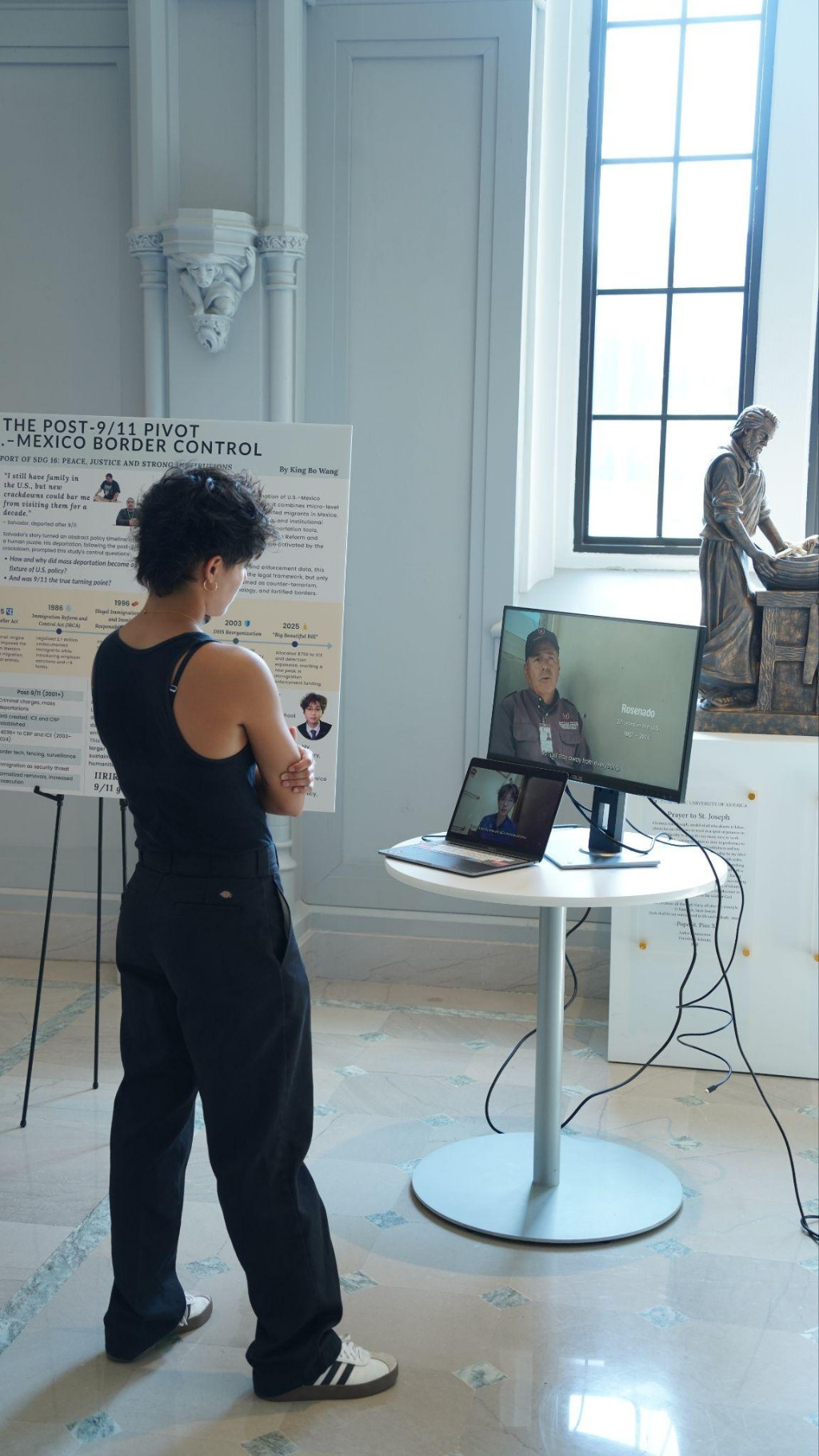

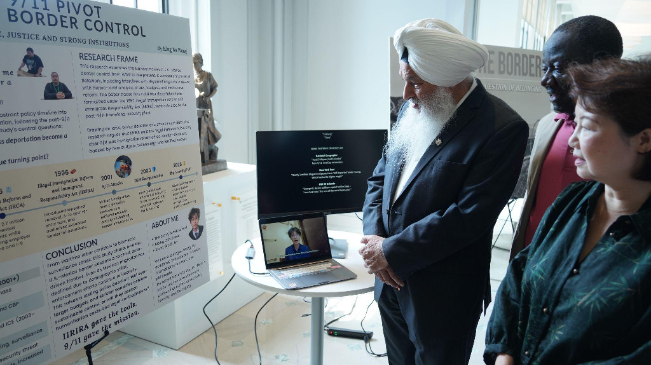

At the international exhibition “Global Youth Dialogue on the Future through Innovation: Voices of Impact – Youth Ideas for SDG Solutions,” co-hosted by UNESCO and the Peace Center, King Bo was selected as one of the participating young artists. The exhibition invited submissions from youth around the world, each presenting innovative projects focused on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). After a competitive selection process, only a limited number of works were chosen to be showcased.

King Bo attends The Stony Brook School (SBS) in Stony Brook, NY, an independent college preparatory school where the motto “Character Before Career” guides everything they do. In this community, students are encouraged to value integrity and empathy alongside academics, and are inspired to listen to different voices, explore the past, and express themselves through art. With the support of his teachers and classmates, King Bo developed a genuine passion for history, understanding others’ perspectives, and creative expression, giving him both the curiosity and confidence to use his talents to address social issues and tell meaningful stories.

The final exhibition showcased over 60 innovative projects, covering topics such as clean energy, educational and gender equality, smart cities, and sustainable development. This event provided an important platform for young people from diverse backgrounds to share ideas and collaborate on global challenges. As a 17-year-old creator, King Bo’s participation reflects both his active interest in social topics and his dedication to creative expression.

During the exhibition, King Bo engaged in discussions with experts from United Nations agencies, international organizations, urban planning groups, and research institutes, gaining valuable insights into both theory and practice. As a youth participant, his work demonstrated the important role that young people can play in addressing global challenges and contributed to international dialogue on sustainable development.

His inclusion in the exhibition affirms the value of his creative perspective. It represents a meaningful opportunity to share his ideas in a broader stage, while encouraging further exploration of social issues.